As a camp professional, I can’t begin to guess how many times friends, camp parents, board members, colleagues in the community, or the UPS guy have told me how lucky I was to have a camp job — and how they wished they could come and enjoy all the fun and games. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, I would smile and agree that the work is easy and always a hoot with only occasional hiccups. On reflection, that might not have been the most intelligent approach, as it distorts the true picture of the job and contributes to a perceptual issue by avoiding the reality of long hours, intense pressure, and challenging situations. And full disclosure: I left direct service over a decade ago, and my observations as a consultant are that things have only gotten tougher.

While we can debate the perception versus reality of year-round camp careers, I struggled to find research that speaks to the impact of these jobs on our well-being. What are the psychosocial and physical effects of year-round working in the camp industry? Is a field promoting wholesome lifestyles a healthy place to work for the talented souls who oversee these programs? What does it do to the mind and body, to relationships with family and friends, and how can we mitigate any potentially harmful elements?

With this in mind, I created a survey and distributed it via social media to discover the issues and access potential solutions. I assumed a solid response rate might have been 50 to 100 people. The actual number of people who participated was 452; more would have come in had I not closed the survey! That degree of participation indicates that I may have struck a nerve.

I have long suspected that a crisis is heading our way that will challenge the field to its core, and the survey results appear to support this thesis. We are at a critical juncture where we must urgently consider how to attract and retain the next generation of year-round talent. Yes, we can look at specific national issues — COVID-19, inflation, rising violence, political discord — and understand how they have impacted our industry. While in no way diminishing the impact of these issues or the pain they have caused, I believe each merely magnified an already existing problem. The changes to our industry have been coming for many years and are now more apparent than ever. It is time to see through the fog and recognize some of the root causes of why we may struggle to keep a viable workforce ready, willing, and able to take the mantle of leadership at our storied camp institutions. The results of this nonscientific survey do serve to illustrate the concerns and provide fodder for your internal conversations.

First, here are some key demographic data points from the survey:

- Nonprofit overnight camps comprised 60 percent of those who responded, 23 percent were nonprofit day camps, 12 percent were for-profit overnight camps, and 5 percent were for-profit day camps.

- Nonreligious camps represented 54 percent, and religious or faith-based represented 27 percent.

- Thirty-three percent of respondents identified as part of a movement, such as YMCA, JCC, or Girl Scouts.

- Respondents included the following job categories: camp director (40 percent), assistant camp director (18 percent), CEO/executive director (21 percent), administrative (operations, registrar, accounting, etc.) (7 percent), and owners (4 percent). The remaining 11 percent was split among fundraising, marketing, and facilities.

- Gender — 66 percent identified as women, 32 percent as men, 1 percent as nonbinary, and 1 percent preferred not to answer.

- Length of service at their current organization (excluding seasonal employment) was as follows:

|

Less than 12 months |

9% |

|

1 to 2 years |

15% |

|

3 to 5 years |

24% |

|

6 to 9 years |

17% |

|

10 - 19 years |

18% |

|

20 years plus |

17% |

So, with these demographics setting the table, let’s explore answers to the more qualitative questions.

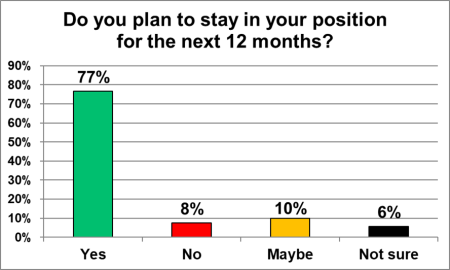

The survey asked if the person planned to stay in their current position for the next 12 months, and 77 percent indicated they planned to stay (see Figure 1). However, this may present a skewed picture. The camp industry has seen massive turnover during the past five years, and the preceding question revealed that almost 50 percent of respondents had been in their current role for only five years or less — which is remarkable for a field heavily reliant on intergenerational relationships. This likely signals that the days of the 20- and 30-year camp director are gone or fading fast.

Figure 1

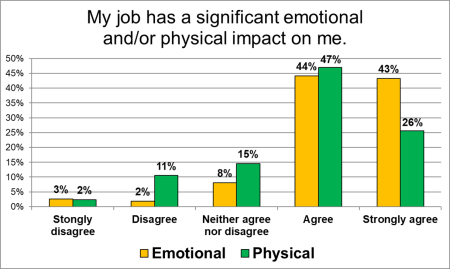

Those who answered anything but yes (24 percent) regarding staying in their position, were asked what the primary reasons might be to leave their current employer. Fifty-seven percent indicated work-life balance as the primary challenge, followed by compensation (52 percent) and organizational culture (51 percent). The fact that work-life balance was a primary rationale should strongly resonate. This underscores the crucial need for self-care and balance in our industry. Combine this with emotional and physical impacts (see Figure 2), where 87 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their work had a significant emotional impact, and 73 percent said the same about the physical toll the job takes.

Figure 2

One not entirely unexpected finding was that despite their challenges, 85 percent of respondents expressed a strong loyalty to their organization. This counterintuitive reality suggests that one can struggle with the job but still have a deep affection for one’s workplace. The narrative comments further shed light on this, with 49 percent being negative, 25 percent neutral, and 25 percent positive (see sidebar for sample comments).

|

Sample Narrative Feedback

|

Despite the challenges, the survey also revealed many positive aspects of the camp environment. Scores in areas such as supervision and closeness of colleagues were overwhelmingly positive. Many respondents felt that the team they work alongside is essential to their success and why they stay. Moreover, when asked if they find the work fulfilling and meaningful, an overwhelming 95 percent indicated that they do.

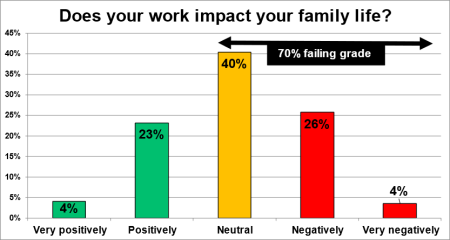

However, when asked about the impact on one’s family life, respondents provided a stark reminder of the reality — fully 70 percent indicated either neutral, negative, or very negative as their score (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

This is not a sustainable trajectory, and while other career pathways might register similar scores, camp has one core ingredient that the others do not: we care for, keep safe, educate, and entertain other people’s children and young adult staff. This tremendous responsibility puts the reality of shifting expectations, social norms, discipline, politics, communicable diseases, and many other elements impacting our world more dramatically into focus than other business sectors. Thinking back 20 years, how many of us expected pressure to upload hundreds of photographs, have health facilities staffed like urgent care centers, or staff who sign and then renege on contracts, or just don’t show up? Who would have thought we would encourage staff to use their phones for inter-camp communication or have parents demanding security plans or nutritional guides? The world has changed dramatically, sometimes for the better, but not always, and the impact of these dynamic shifts falls directly on camp professionals to contend with and solve for.

To ensure we are all on the same page (and perhaps drive home the scale of the challenge), here are two final measures: a simple stress test and a net promoter score.

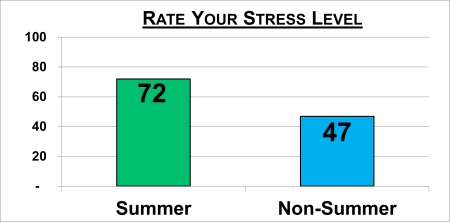

Survey respondents were asked to rate the difference between summer and nonsummer stress on a scale from zero to a hundred (see Figure 4) The average stress level indicated was 72 during the summer and 47 during the offseason. (A human being operating at a stress level of 72 for 10 to 12 weeks full-on is not healthy.) And our next generation of camp professionals don’t need to be told this — they are intelligent, thoughtful, and appear better at understanding the importance of work-life balance than their predecessors. They will vote with their feet and not take or retain jobs that negatively impact their quality of life.

Figure 4

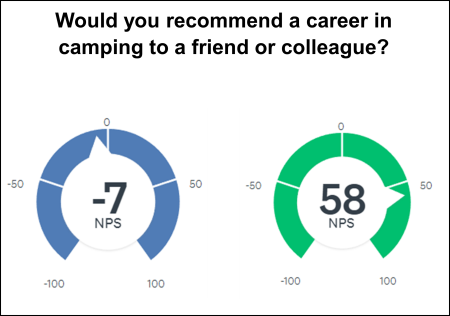

For the final survey data point — to determine a Net Promoter Score (NPS), today's gold standard for businesses to measure and track customer satisfaction (Bunker, n.d.) — respondents were asked if they would recommend a camp career to a friend or colleague. Given an NPS score range from -100 to +100 (the higher the score, the better), the -7 with regard to summer camp is a significant concern (see Figure 5) that paints a less-than-rosy image for the future, especially when compared to all nonprofits (the closest comparison I could find to our field).

This should serve as a wake-up call for some tough yet essential conversations about our industry. Camps can and will fail without talented, dedicated, energetic, and compassionate year-round staff. Moreover, staff who know their clients engender trust and loyalty, so we must take this seriously. Most importantly, it is not too late. The sky has yet to fall, and there is still hope.

Figure 5

In framing any conversation regarding work-life balance or job satisfaction, we must recognize that our field is built on relationships that can stretch back from camper to parent, grandparents, and beyond. When that timeline is interrupted or disturbed, and there is a lack of continuity, then recruitment and retention of campers and staff can suffer. Relationships are everything in the camp world, and these are lifestyle jobs. If the lifestyle diminishes past its opportunity cost, we are in trouble.

So, what to do? Here are some recommendations and action steps to consider as you dig deeper into your unique circumstance as a professional or volunteer:

Take the professional lifestyle and stress issue seriously, and do not dismiss it as a generational issue we all face at some point. Up-and-coming camp professionals are acutely aware of the importance of our field of service. However, this rising generation understands work-life balance better than prior cohorts and will act upon it when push comes to shove. Acknowledge it and discuss the issues openly as a camp team without pressure or shame. Avoid “back in my day” commentary; it won’t resonate with younger camp professionals, who will see it as irrelevant to the future.

Narrative comments in the survey indicated a lack of understanding of the role of camp professionals by board members and volunteers. Please share this article with them and engage in as open and transparent a conversation as possible. Bring a third-party consultant in to facilitate the discussion and get a realistic handle on the issue without judgment or blame. There is a fundamental fiduciary expectation that the organization’s resources are used wisely to ensure maximum benefit, and staff is the most valuable resource any camp has. Do not overlook the power of prevention versus trying to cure a festering problem that hides below the surface.

Hours matter, and so does compensation. Do the math and add up those 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. days with a few days off over the weeks of summer. Both day and overnight camp people work tirelessly. Some camps have made bold decisions and, based on the hours worked during the summer, they work a four-day week during the rest of the year. (And don’t exclude weekend recruitment events; they should be included in the count). Even then, your math will likely indicate the organization is still getting a bargain and not fully reimbursing the accrued time during the summer. If you close the office for everyone and insist they take time off, you will see the difference in attitude, morale, sickness, recruitment, and retention.

Stress, which can weaken your immune system, impact hormone levels, and is associated with unhealthy behaviors (Canadian Cancer Society, 2024), is dangerous in sustained doses. So, consider providing concierge medical care and mental health support for the team and individuals. Normalize this and remove the stigma associated with this type of support. If you can, pay for gym memberships and include the time to exercise in the workload. Discuss and determine how much stress one employee should absorb, and staff your camps to thwart the long-term impact on the individual and those they love. If you have a medical committee or advisor, engage them. If you do not, find a camp parent who is a medical practitioner and engage them in the conversation. Alternatively, bring in a third-party consultant to facilitate the discussion.

Provide year-round staff with a sabbatical opportunity. For example, employees might earn a two-month paid sabbatical for every five years served. The only expectations are to return with their batteries fully recharged and to share what they’ve learned during this period.

Let’s be honest; there is so much more to learn, discuss, and do to help ensure that our camps remain vibrant and vital for another hundred years and more. Today’s camp industry is not the same as it once was — and that is OK. Yet, we are still the only place that provides these immersive experiences where children and young adults can test, fail, win, lose, explore, grow, dance, sing, and reinvent themselves. We cannot let that disappear from our collective consciousness. Camp must thrive, and it will only do so if we care for the carers.

Finally, this discussion has merely grazed the surface of this issue. My research is quasi-scientific, and while the survey sample was robust, there is so much more to do in this space. We must focus intently on this issue and do more to move the stress needle down and ensure we are here and thriving for a long time — the world needs camp more than ever!

Photo courtesy of Camp Sugar Pine Girl Scout Camp, Arnold, CA.

References

Bunker, A. (n.d.). What is NPS? The ultimate guide to boosting your Net Promoter Score. Qualtrics. qualtrics.com/experience-management/customer/net-promoter-score/

Canadian Cancer Society. (2024). Does stress cause cancer? cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/reduce-your-risk/myths-and-controversies/does-stress-cause-cancer

David Phillips is principal of Immersive1st, a firm specializing in fundraising, planning, and visioning; governance; acute organizational analysis and program creation; and implementation and evaluation. A lifelong communal professional, his passion is doing important things with good people who make a difference. He is a frequent speaker and presenter at conferences and an author on various youth-related topics. He holds an MSW in Social Work from the University of Pittsburgh, focusing on community organizing and development. David can be reached at [email protected]